By Chandler Haugh

The European Defense Agency (EDA) signed a €10 million military research project into being earlier this year. The research project? To see if a small constellation of two to four satellites can be maneuvered from Low Earth Orbit (LEO) down to Very Low Earth Orbit (VLEO) and back again. They are calling it LEO2VLEO and it will help answer some of the questions the space industry has been asking about the value of VLEO orbits.

What is it?

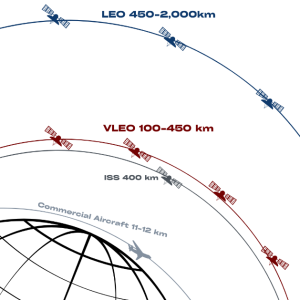

How low can you go? Very low, apparently, as researchers have finally determined that this new frontier is worth industry investigation. Research into VLEO craft has been ongoing for over a decade, and establishing constellations in these very low Earth orbits could change how we communicate, gather intelligence, and complete research. VLEO satellites are on the horizon (literally) for several companies in 2024 and are being described more broadly as encompassing orbital paths 100-450km away from Earth’s surface with most objects in the 200-300km range. Compare this to LEO, defined as within the 450-2,000km range. The International Space Station, for example, technically falls within a VLEO orbit at 400km above Earth’s surface. VLEO satellites offer benefits unique to their orbit, which is why research like LEO2VLEO will be exciting to watch.

How low can you go? Very low, apparently, as researchers have finally determined that this new frontier is worth industry investigation. Research into VLEO craft has been ongoing for over a decade, and establishing constellations in these very low Earth orbits could change how we communicate, gather intelligence, and complete research. VLEO satellites are on the horizon (literally) for several companies in 2024 and are being described more broadly as encompassing orbital paths 100-450km away from Earth’s surface with most objects in the 200-300km range. Compare this to LEO, defined as within the 450-2,000km range. The International Space Station, for example, technically falls within a VLEO orbit at 400km above Earth’s surface. VLEO satellites offer benefits unique to their orbit, which is why research like LEO2VLEO will be exciting to watch.

What’s the big deal?

Satellites in VLEO offer opportunities for low-latency transmissions, shorter life cycles, lower costs, higher resolution images, and a “self-cleaning” feature. However, interested parties must act fast to secure their spot. For comparison, a medium Earth orbit constellation can use an expanse of 33,000km worth of Earth’s orbit to deploy constellations. Those wanting to take advantage of the very low Earth orbit only have 350km of orbit to share, and the race to dominate this new frontier has already begun.

Direct-to-device (D2D) technology is in high-demand as the number of devices per person continues to increase, straining global communications infrastructure. VLEO constellations could offer continuous coverage with lower latency than subsea cabling. Such efficient transmissions would enable the fast rural coverage that many terrestrial broadband providers are struggling to establish. Transitioning from subsea or terrestrial to space could also provide better protection to communication infrastructure. Currently, subsea cabling is threatened by both nation-state and non-state actors such as Russia and the Houthis, respectively.

VLEOs could also offer higher resolution imagery for Earth observation. Positioning observation satellites closer to Earth produces clearer imagery at lower cost. Scientists at NASA explained that smaller, cheaper telescopes combined with a lower orbit would produce imagery that can be used for military intelligence, weather tracking, and climate research.

Nearer Earth orbit also reduces launch costs. Researchers at Bauman Moscow State Technical University highlighted the difference in launch costs between geostationary satellite orbit (GSO) and LEO orbits. VLEO objects offer lower costs per launch vehicle by 100% when compared to their GSO peers. Where there could be one GSO satellite launched per vehicle, one can launch 100 LEO satellites. One can further lower the cost of launch if partnerships form to fill launch vehicles.

While a shorter lifespan may seem unappealing at first glance, launching and deorbiting quickly means more opportunity for innovation and testing. With faster turn-around times on hardware life cycles, the “very” in VLEO can make cutting-edge technology more widely available as hardware can be produced and tested on-orbit on an accelerated timescale. Typical life cycles for satellites beyond LEO are between 10-20 years. When developing hardware and software that can remain secure and effective, the speed of innovation quickly eclipses technology that is no longer cutting-edge when launched. The resulting accelerated pace of hardware development creates an opportunity for off-the-shelf technology, effectively lowering the cost of entry. Upgrading hardware and software more quickly also allows for improvements in security and operations.

One of the biggest issues facing participants in the modern space race is orbital debris. Researchers are claiming that VLEO offers a “self-cleaning” feature. This means that if a satellite is to deorbit in VLEO, the atmospheric density is such that debris would decay rapidly. The atmospheric drag at low altitudes virtually guarantees that nothing will stay in VLEO for very long. This same atmospheric density means that whether or not a deorbit is planned, no satellite will be “stuck” in orbit for years. This coupled with the fact that VLEO sats tend to be small means they all burn up harmlessly on reentry.

Who is playing satellite limbo?

Having fallen behind in the LEO race, China is investing heavily in VLEO. The race is on to see who can take the competitive edge in this minimal orbital strip before it begins filling up like LEO. There are 8,000 active satellites in Low Earth Orbit, most owned by United States entities such as SpaceX/Starlink and Amazon/Project Kuiper, and European entities such as One WEB/Eutelsat. There has been a surge in launches over the past five years, with 450 objects launched in 2018, to 2,600 in 2023. China has already begun launching satellites into VLEO. Starting in mid-2023, Galactic Energy (a Chinese startup) launched the Qiankun-1 to test the high resolution image quality that VLEO is expected to provide. This is the first satellite of 300 planned for launch by 2023 comprising this Chinese VLEO constellation. China’s goals for VLEO were discussed at the China Commercial Aerospace Forum, announced by China Aerospace Science and Industry Corp (CASIC), which said that “ultra-fast remote sensing and communication services” are pushing China to invest in VLEO constellations.

Simultaneously, the United States is funding VLEO research through Air Force Ventures’ Tactical Funding Increase (TACFI) program. Earth Observant Inc. Space (EOI Space) and Albedo are two of the companies being funded by the TACFI program to research and develop VLEO solutions for GPS and imaging. Also within the United States, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is looking to provide funding to companies able to “investigate innovative approaches that enable revolutionary advances in science, devices, or systems that optimize mission capability and lifetime” within VLEO. US-based, Starlink has plans to expand its LEO constellations into very low Earth orbits. A Starlink application to the ITU was denied as moving Starlink satellites into VLEO could interfere with the orbital path of the International Space Station. Starlink’s hope was that a VLEO-based constellation would reduce the latency of its current services from above 30 milliseconds to below 20 milliseconds. As China has already begun deploying in VLEO, other nations such as Japan, Russia, Korea, and European nations led through the European Space Agency, are beginning research into the opportunities of low orbit and what it could enable.

Is it too low?

The current expectations of leaders in the field are that cost will decrease when production increases, but there is still the possibility that VLEOs could be just as expensive as their higher-orbit counterparts. Shorter life cycles and a “self-cleaning” feature mean that there is a higher likelihood of haphazard satellites and failed launches. Higher atmospheric drag due to the lower orbit could lead to unexpected de-orbits. With so many satellites per constellation, the number of reserve satellites prepped for launch would be greater than a constellation in MEO (Medium Earth Orbit) or GSO. A shorter life-cycle plus higher likelihood of unplanned de-orbit would require more satellites to fill and backup a constellation, and more launches. Only time will tell what the true cost of a VLEO constellation will look like, and it will be up to those with the capital to decide if the benefits outweigh the costs.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent.