By Christian Kuzdak

NASA simulation of orbital debris around Earth demonstrating the object population in the geosynchronous region

When Sputnik I entered low Earth orbit (LEO) at 18,000 miles per hour on October 4, 1957, the satellite left behind a world fundamentally changed by its achievement. It also left behind a 7.5-ton R-7 second stage rocket which became the first ever piece of space garbage.

Almost 70 years later, the number of active satellites in orbit exceeds 8,000, with capabilities ranging from communications and navigation to climate monitoring and astronomical observation. In recent years, the commercialization of space has yielded breakthroughs, particularly in LEO, offering competitive consumer broadband speeds, better Earth imaging, and use cases straight out of a science fiction novel. But as the number of objects in space increases, particularly as companies begin to climb over one another to deploy their own satellite constellations, the negative externalities of this frenzy are becoming apparent.

As the Union of Concerned Scientists notes, a fragment of junk as small as 1 cm in diameter can cause serious damage to a satellite. NASA estimates that there are well over half a million objects larger than 1 cm currently in orbit, on average traveling about 10 times the speed of a bullet. Others suggest there could be twice this many.

These circumstances pose not only an individualized risk to satellites in orbit, but an existential risk to humanity’s future as a spacefaring species. Because a collision will itself generate additional debris, in a sufficiently dense orbital environment, a single collision could trigger others, which in turn trigger still others, producing a domino effect commonly referred to as the Kessler Syndrome after NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler. The resulting debris field could make entire orbits unusable, or even impassable, effectively ending human space exploration.

Consequently, multiple government agencies and scientific organizations have endeavored to catalogue and track as many of these hazards as possible. But even if we could track every piece of dangerous debris (we cannot), situational awareness would not be enough. Debris is increasing at an alarming rate, and little is being done to slow its creation, much less reduce the overall number of objects. Instead, satellite operators continue to propose thousands and thousands of new satellites, relying on a dangerous mixture of techno-optimism and market mysticism to provide unspecified solutions to the problem at some later date.

Sputnik’s spent rocket was little more than a footnote at the dawn of the space race, reentering the atmosphere as anticipated less than two months after launch. Today, we cannot afford to relegate space debris to the margins.

The Scale of the Problem

Nobody is really sure exactly how much debris is already in orbit. Estimates for objects greater than 1 centimeter in diameter range from around half a million to over one million. Of these, there are perhaps 55,000 which we can conceivably track, and around 27,000 which are currently tracked by the United States’ Space Surveillance Network. Thankfully, this covers the most catastrophic possible collisions, but likely accounts for somewhere between 2-5% of all problematic debris.

The issue becomes all the more concerning when one realizes just  how quickly the rate of satellite deployment has increased, with no sign of slowing. The number of satellites launched in 2023 was nearly fourteen times the number launched in 2013, itself a record setting year. SpaceX alone now boasts plans for a constellation of 42,000 satellites – almost three times the number of objects put into space since 1957. Its competitors in the United States, China, and Europe are not far behind.

how quickly the rate of satellite deployment has increased, with no sign of slowing. The number of satellites launched in 2023 was nearly fourteen times the number launched in 2013, itself a record setting year. SpaceX alone now boasts plans for a constellation of 42,000 satellites – almost three times the number of objects put into space since 1957. Its competitors in the United States, China, and Europe are not far behind.

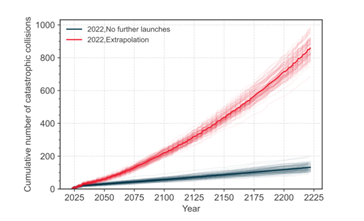

Worse still, the European Space Agency (ESA) projects that we have already reached a critical density in orbit such that debris would continue to increase over the next 200 years and beyond, even if we were to stop launching new objects entirely. Since we are unlikely to do that, we can instead expect a dramatic rise in both the creation of objects greater than 1 centimeter in diameter and the likelihood of “catastrophic collisions” (collisions that cause the complete destruction of both the target and impactor).

Worse still, the European Space Agency (ESA) projects that we have already reached a critical density in orbit such that debris would continue to increase over the next 200 years and beyond, even if we were to stop launching new objects entirely. Since we are unlikely to do that, we can instead expect a dramatic rise in both the creation of objects greater than 1 centimeter in diameter and the likelihood of “catastrophic collisions” (collisions that cause the complete destruction of both the target and impactor).

All this is to say that despite the vast distances at play in orbit, low Earth orbit in particular is becoming a combination shooting gallery and ticking time bomb.

Markets and Negative Externalities – The Role of the Regulator

The problem is a familiar one. Industry, disaggregated as it is, and interminably focused on quarterly returns, is unable to marshal a response to the slow and steady depletion of a common good. Faced with a problem like orbital debris, the only solutions that the market can offer are ones that promise to turn an additional profit. Accordingly, we are seeing the advent of the so-called in-space assembly and manufacturing (ISAM) field, which has produced some truly inspired concepts for craft capable of refueling and deorbiting satellites, as well as collecting wayward debris. However, ISAM craft capable of meaningfully addressing the existing orbital debris challenge may be years from commercial viability, assuming they work at all. Debris removal technologies are exciting, but for the moment remain borderline fantastical, totally fail to meet the current challenge, and may not even be profitable anyway. We need to act today, and the only feasible solutions today are policy solutions.

Orbital space is a resource like the air we breathe or the electromagnetic spectrum over which we conduct our wireless affairs. As such, it requires stewardship by experts answerable to our democratic processes and driven by the common good. It is also a resource that transcends borders, making international approaches as important as domestic ones.

The FCC has shown awareness of the growing threat, but its efforts to accelerate the pace at which objects enter space by streamlining satellite licensing procedures and forming a dedicated Space Bureau have taken center stage over maintaining a sustainable environment in space. The 2022 update to existing orbital debris rules that requires that decommissioned satellites deorbit within five years was a welcome step in the correct direction, and the subsequent May 2024 decision to further reexamine orbital debris rules promises to strengthen those regulations. But this is not enough.

The FCC cannot, and should not, act alone. The FAA, Department of Commerce’s Office of Space Commerce, NASA, and others have a role to play whether as experts or regulators in this space. NASA, in particular, has spent considerable time and effort in developing a Space Sustainability Strategy, released earlier this year. That strategy identifies five key challenges:

- Differing sustainability frameworks across the space community;

- Insufficient models and metrics for accurately understanding the orbital environment;

- Uncertainties in the space environment and operations at issue;

- Organizational priorities in tension with sustainability; and

- A lack of coordinated global response to the threat.

Some of this comes down to good old-fashioned hard work. Scientists and engineers need to put their heads together to find ways to better understand and represent the wildly complex dynamics of objects in orbit, as well as better ways to identify and track debris. But even a perfect understanding of the orbital environment and the way objects therein interact would be insufficient absent sustained communication and coordination among satellite operators. A future in which operators must contend with 193 different sustainability frameworks is simply untenable. Some are bound to be better than others, and a failure to share information is guaranteed to lead to disaster. Currently, some operators that launch outside the United States are not required to (and do not) share their orbital debris mitigation plans. These hidden plans could contain massive risks easily corrected by peers, or smart innovations of which others are robbed.

What Now?

The last century of human history has challenged us with problems of unprecedented magnitude and global impact. Orbital debris is just such a problem. Technology will be part of the answer, but governments must act prudently, and in a spirit of cooperation if we have any hope of avoiding catastrophe.

Building on work like NASA’s Space Sustainability Strategy and the FCC record on orbital debris, national regulators should continue to better understand the orbital environment and curb the excesses of gung-ho industry operators. Simultaneously, governments must work multilaterally toward the same ends, and to create universal standards for both information sharing and safe and sustainable behavior. A painful part of this process will be determining and enforcing limits on the number of objects in a given orbital plane.

Human space flight captures, perhaps better than any other activity, the boundless optimism of the human spirit, as well as the height of our technological achievement. Detractors may see sustainability regulation as an impediment to these aspirations, but they are in fact the opposite. They are a guarantee that developing countries, future generations, and innovators everywhere will continue to have the resources necessary to contribute to and participate in the utility, discovery, and wonder of space flight.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent.